National Foundation Day in Japan on February 11th every year is a rather unassuming, strangely uncelebrated holiday that allows most people to have the day off in the middle of February after a long bout of work since New Year’s. Most countries that celebrate the day of their founding have huge celebrations across their lands, but not Japan. Why? Well… It’s all because of the holiday that started it all… Kigensetsu or Foundation of the Empire of Japan Day!

Amazon Affiliate Linked Japanese Goods Shop

February 11th Every Year

Transformed into

Kenkoku Kinen no Hi 建国記念の日 1966 to Present

From

Kigensetsu (紀元節) 1873 -1945

Let’s Talk About Kigensetsu

Founding Legends and their Applications

What was the basis of Kigensetsu?

Well, in short, they used to have a hugely popular national foundation holiday called Kigensetsu. But unlike most countries that celebrate a founding based on actual historical events, the Japanese founding legend was used as propaganda to condition children in public schools to unquestioningly obey and have absolute loyalty to emperor Meiji and his progeny from 1873 until 1945. The

NihonShiki and

Kojiki tell how in the year 660 BC all Japan, or the country at that time (as Eastern Honshu was definitely still under control of the Emishi tribes), was united through conquest by someone known as Jimmu. This is dated as the beginning of the empire of Japan. Or, according to one theory, this date was selected by later chroniclers as an auspicious time for great change according to the ancient Chinese calendar in use at the time.

Who was Jimmu?

Jimmu was supposedly from the island of Kyushu, and sailed up the inland sea to attack the Yamato tribe. Another family member attacked the Yamato from the west in the area of present day Osaka first, but was not successful. Jimmu led a force from Ise, on the other side of the Kii peninsula near present day Nagoya, and attacked the Yamato from the east. He was successful. From the Kii peninsula west through the inland sea to Kyushu, the land was his. And so he was declared emperor, according to the

NihonShiki and

Kojiki.

After Jimmu Until the 3rd Century AD

After emperor Jimmu (who incidentally lived about 125 years, according to the

NihonShiki and

Kojiki), according to legends and later chronicles, were a series of emperors who reigned from 31 to over 101 years each before the Kofun period (roughly year 300 current era). Ten of these emperors reigned over 50 years! It is quite possible that some emperors might have been forgotten and their reigns rolled into the next emperor that was remembered.

On Legendary “Events”

Like the legend of the Trojan war, the events of emperor Jimmu’s reign are some what plausible, but there isn’t much hard evidence. There could have been a chieftain from Kyushu who conquered the coastal areas of the inland sea region and the Yamato peoples around present day Osaka in the way attributed to Jimmu. The legend is rather specific about who did what and where. The later chroniclers who were transcribing the oral traditions may have felt that they needed an impressive date for the founding of “The Empire of Japan”, so they embellished the story and came up with the founding year 660 BC. The chroniclers of the

NihonShiki and

Kojiki may have felt some title envy as well with the Chinese as Jimmu seems to have been a chieftain over other chieftains, which I think is technically a king… but I digress.

Influence of the Emperors in Japanese History

For most of Japanese history the emperor was an important religious and political figure. But there were things that superseded their fame and authority, such as distance from the court and the time it took to send messages out. Therefor, local deities and commanders had a lot more sway over the daily lives and respect of the people. The day to day loyalties were definitely more focused on the local gods and old gods such as Amaterasu Omikami (Great Divinity Illuminating Heaven), the Sun Goddess, whom the emperors were supposed to be descended from. The emperors were highly respected and everyone thought of them as the head of state, but they weren’t the top gods and people would fight for their local warlord first. This was because there was no way or people in the countryside to know that the message from the emperor was really from the emperor as he rarely came out of seclusion in his capital and they were illiterate. However, Toshi-the-local-guy-they-all-knew, standing right in front of them, would definitely be giving them a very real order and was the one who paid them anyways.

Shogunate Decentralisation

When the Tokugawa shogunate was eventually overthrown and emperor Meiji was restored as the head of state, this lack of central authority and personal loyalty to the emperor was kind of a problem. During the Tokugawa shogunate Japan was ruled as a kind of confederacy. On top was the Shogun in Tokyo. The Shogun had his personal domain, and they were surrounded by loyal kind of kings, called Daimyo. And then on the periphery were lots of lesser in loyalty Daimyo. These Daimyo ruled their domains pretty independently, but they couldn’t go too crazy with their freedom because they had to live half the time in Tokyo, away from their lands. Also their family had to reside in Tokyo pretty much all the time as essentially very well-to-do hostages. The Tokugawa shogunate is considered a time of peace, because the previous one hundred years of civil war was so over the top violent. However, there were petty wars and intrigues going on all the time amongst the various Daimyo.

Bringing the country together… under the emperor

This loyalty to the local daimyo was a problem for the early Meiji government. So they felt it necessary to create national unity. The unifying figure was decided to be the emperor himself. In 1872 the first holiday of The Founding of the Empire of Japan Day, Kigensetsu, was declared to be on January 29th, 1873. Incidentally, January 29th of that particular year just happened to be the same date as Lunar New Year under the ancient calendar that had just been abolished for the fancy new Gregorian calendar. Most people across the country were confused and just celebrated it as Lunar New Year. So the Meiji government officials decreed that February 11th was the really real historically accurate date of the ascension of Jimmu to emperor of all Japan. They never really got around to giving any evidence for this decision. Today it is just pretty much understood that they made it up.

And then there was Kigensetsu

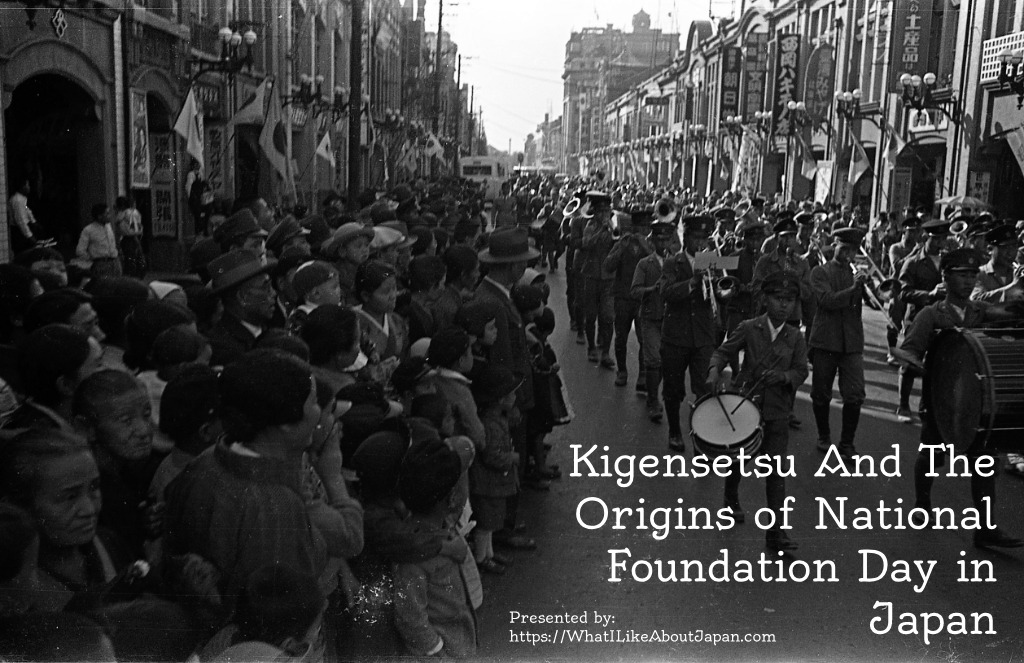

Kigensetsu, by all accounts, was a really good time! There were celebrations and festivals, parades, grand speeches and public reading of poetry, sporting events and kids would get sweets. It was what you would expect from a national holiday for the creation of the state. Apparently the high point of the festivities was group prostration to the picture of the sitting emperor. Then the people would listen to speeches about how the Japanese were especially good because they had god-emperors as rulers. This last part was kind of a model for the rhythm of the school children’s day.

Spread of emperor worship in Japanese primary education before 1945

When Japanese children went to school they would begin class by bowing to a picture of the emperor in the class room. At graduation ceremonies the students would listen to the principal give a speech about how Japanese were special amongst the world’s people because only they had a living god as an emperor. This godhood apparently also made the Japanese emperor especially virtuous. Because the emperor was a god they must unquestioningly obey all his commands and edicts. Today Japanese children just bow to their teacher at the beginning of class and maybe listen to the principal give a speech at graduation ceremonies on how Japan is a special nation because it has four seasons (this last one is from my own personal experience and has popped up with widely different people in totally different geographic areas and times, so I think it must be widespread across the country).

The slow spread of emperor worship before 1945

Kigensetsu was often mistaken for other events

At first Kigensetsu’s message didn’t really reach all over the country because of the lack of primary education for quite a while. Many places in the Japanese countryside celebrated local gods instead for a time. One town mayor, as late as 1900, thought it was the celebration of emperor Meiji’s birthday. But when a public school was built in his town and the mayor learned of the true nature of the holiday he corrected himself from thereafter. The spread of emperor worship throughout Japan went hand in hand with the spread of primary education. By 1905 everybody was more or less on the same page that the emperor was a kind of living god and embodiment of all the country who commanded and deserved unquestioning obeisance and unwavering loyalty above all others. The process of coming from, “Who is that guy?”, to “Everybody kowtow to the painting of the emperor at the same time” took approximately 20 years.

The transformation of Kigensetsu

In 1945, after the end of WWII, the American General Headquarters in Tokyo cancelled any further observances of Kigensetsu. Either by coincidence or clever design, McArthur approved the draft of the Japanese constitution on February 11th, 1946. However, a lot of people really missed the old holiday. After much public discussion it was decided to bring it back as Kenkoku Kinen no Hi, or National Foundation Day.

National Foundation Day Today

Kigensetsu Re-imagined and unfunded

National Foundation Day is a much welcomed day off after more than a month of solid work without a holiday since New Year’s. The overwhelming number of people in Japan just use the time to relax. It seems that most young Japanese people today don’t really even know which holiday this is; its just a day off work to rest and play. There are some festivities at some shrines. Specifically, Meiji Jingu (great shrine), near Harajuku has a parade starting around 10 am at Meiji park that ends around 12:30 at Meiji Jingu. In Nara at Kashihara Shrine in Nara Prefecture, there are also parades and processions because this is the supposed site of Jimmu’s accession to emperorship. It is also rumoured that his as of yet undiscovered tomb is also not for away!

Those who care deeply about National Foundation Day

Hint, They really care about Kigensetsu

Though most people don’t care much at all about the National Foundation Day, there are some people who care very much about it. There are two opposing groups: Uyoku dantai, who are Japanese ultranationalist far-right identifiers, and people who are against a holiday with strong links to emperor worship. Uyoku dantai hold this day in reverence and will be out in force, especially at Kashihara Shrine in Nara. Please be respectful, and probably quiet around them. If you feel inclined to laugh at them and point them out for special scorn, maybe you should just bite your tongue and go someplace else. Personally I have never met with any violence or aggression from these guys, nor have I ever felt I was in danger at any time, but I also just treated them like every other person, too. People ethically against the holiday may be out and about protesting the existence of the holiday because of the strong links to emperor worship and the atrocities that way of thinking led to in WWII. These people will most likely be protesting at government offices, and not counter protesting at shrines where Uyoku dantai might be present. However Uyoku dantai might drive around their general vicinity in their “Genki Vans” blaring ultra-nationalist songs and old imperial anthems at painfully loud volumes for hours at a time (they must drive around wearing earplugs in those things!). But, they may also just be driving around random places doing the same thing as well on this day. Both groups are small minorities compared to the number of people just trying to enjoy themselves. The official government position is that the holiday should be a time to show a love of country, but they don’t provide any financial support or planning for any festivities.

Have Fun! Stay Safe!

So if you want to enjoy National Foundation Day just go out to your local shrine, or the biggest one in your area, and see what is going on. Remember, festivities of some sort usually start at around 10 am.

Image thanks to 李火增, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

About the Author

Pjechorin

Facebook TwitterI have lived and worked with my family in Japan since 2005. For many years I have been interested in the very practical and creative side of Japanese culture. In my free time I travel around, enjoy hiking in the countryside and cities, and just generally seeing and doing new things. This blog is primarily a way for me to focus my energies and record and teach others about what I have learned by experience constructively. I am interested in urban development, and sustainable micro-economics, especially home-economics, and practical things everyday families can do to survive and thrive through these changing times.